|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Listen, Winter 2013 |

| By Ben Finane |

| |

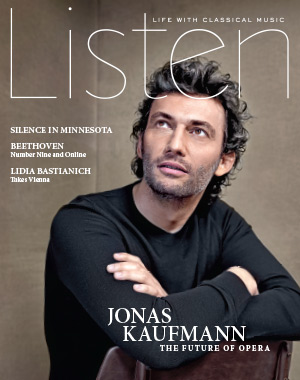

Don't box me in

|

| |

| I've always fought against being put in a box," Jonas Kaufmann tells Listen, "however bright or golden the box may be. It's part of keeping myself attracted to the job." Indeed, the celebrated German tenor has traveled through bel canto, Puccini, Wagner and Verdi — and is set to star in the title role of the upcoming Metropolitan Opera production (see photo on pages 38-39) of Massenet's Werther. Kaufmann gave an interview of unbridled enthusiasm for his art and craft. |

| |

I've

had a sore throat all month that I can't seem to shake. Any suggestions? I've

had a sore throat all month that I can't seem to shake. Any suggestions?

Well, there are the usual things like tea with honey or hot water or

inhaling with some herbal thing, but I think the most important

ingredient is that you eat healthy, that you don't drink alcohol. This

can actually help the most, because of course you can get healthy by

trying to disinfect your throat or something—but what really matters is

your immune system. If that doesn't work, because you're under stress or

whatever, then it will just take forever [to get well]! I hope you feel

better.

Thank you. This leads us to fitness. And I hope

you'll permit me a sports analogy here.

Of course—by all

means!

Before Tiger Woods became a professional golfer,

there were a lot of out-of-shape golfers out there with big bellies who

played professionally. But Woods's success made people reconsider a lot

of things (even how they built golf courses), not least of which was the

base level of fitness required for playing professional golf. Now, I'm

not going to name names, but there are a lot of professional, fat opera

singers out there —tenors, sopranos, baritones, contraltos. And I saw

your tremendous Parsifal at the Met. And this Parsifal was also

tremendously fit. I have to think that in a marathon opera such as

Parslfal, or any opera frankly, that level of fitness is beneficial as a

singer.

There are two ways to see that. One is that it's

always been enough to have a beautiful instrument, so why shouldn't it

be enough today? People would once easily accept, in a semi-staged

performance, singers who hardly looked at each other and never touched

as the [romantic] couple—just because they are singing about love! And

the music is beautiful, so the rest is okay. In our generation, it's a

different take: people want to see something more reflective of reality

than used to be the case in opera. In theater, it's always been a

challenge to be as close to reality as possible. It's a fact that we

need to add something in order to make opera attractive and interesting

and credible. It was certainly never a downside if someone could act on

top of his singing, but it was never required. Then we unfortunately had

the opposite, which is to say people were so keen to see good-looking

people do some crazy things on stage— besides the singing — and that

became more of a focus than the quality of the voice, of the instrument,

the technique. I believe we are back on track, but we now must have the

combination, because you can't turn back that wheel. We need people on

stage that can act and yet can do all the things that normal people do

in their lives outside of singing. And in order to make that happen

—with singing, and with something extra that isn't as natural as

talking—you need to be fit. You need to be [active] because this is very

demanding. And I think that's the ultimate result, and very fortunately

I'm not the only one: there are many, many more out there. And I think

this is the future of opera.

Parsifal is such a

mysterious character in such a fantastical and mysterious opera —at some

points in this opera, time seems to stop. Can you tell me about your

experience with the role?

Parsifal is probably the most

perfect opera by Wagner. If you look at the score and the way he handles

the orchestration and everything, it's just amazing. It's so strong that

it's like a drug: the more you hear it, listen to it, dive into it —

it's not shallow water, it's very deep. It's almost endless. You always

have the impression there's another layer underneath the one you've just

discovered. It's like you're diving for the first time at the Great

Barrier Reef and you cannot imagine that this is all happening and that

there's so much more to discover and you want to stay there for

twenty-four hours, but you only have air for now. So that's the feeling

for us [singers] also, not only for an enthusiastic audience. That makes

it beautiful and unique for us but also tricky, because we tend to be

drawn away by it, too, and it's difficult to keep your concentration and

stay alert because as Parsifal, as in any Wagnerian part or opera,

you're often onstage, acting, being part of the scene, but not singing.

At the end of the first act, as Parisfal watches the whole ceremony [of

the Grail], it's about thirty-five minutes where he doesn't move,

doesn't talk. But you have to be really there, be credible and be

present with all your senses. And that's what makes it difficult. It's

tiring and you can call it a marathon, as you said, though the phrases

that Parsifal sings altogether are probably fewer than many Verdi opera

roles! — but it's really difficult nevertheless. When we did this

[Metropolitan Opera] production I called it 'a transcendent journey'

because I had the impression that we are on this strange cloud, in this

mystery, not knowing exactly what's going on as we're carried away by

these mystical sounds. On the one hand, it's very fulfilling when you do

it, when you have done it; at the same time, it's very demanding because

you need tons of stamina to sustain and to be 'on' a hundred percent.

You started this discussion about sports. It's like being a goalie

in a soccer game with a perfect team — call it Bayern Munich, my home

team. They've won everything possible. And Manuel Neuer is the

goalkeeper for Munich and the German national team. And there's no doubt

that Neuer is great, but he has problems sometimes because his team is

so good. Let's say that for eighty-nine minutes of the game he has zero

to do, not one shot on goal. And then suddenly in overtime there's one

moment where you have to show your excellence to perfection, and if you

screw up this one particular thing everyone will blame you and say 'My

goodness! He has had nothing to do! He has one shot on goal and he can't

hold the ball!' But it's so much more difficult than if the teams are

more equal and you have a lot to do — because that keeps you alive and

focused.

There's a theatrical concept of 'creating a

character' that has been imported into opera. In theater when you create

a character there's Just a script and stage directions. Preparing for a

role in opera, I would say that a score provides more Information than a

script —the composer has fleshed a lot out already with setting text,

dynamics, et cetera. What are the biggest challenges in opera

preparation?

It's somewhat different from preparing a

part for a play because in a play you have all the information regarding

your character: you can read your lines, the lines of the others, read

between the lines, read background information, et cetera.

Moreover in opera you have the [prevailing] interpretation of the

composer, meaning that you can't start from zero: you have to find a way

to interpret this part so that it aligns with the composer's idea. So

you have to find out what he thinks your character is, knowing that the

intention of the music is to underline and support your acting, not to

diminish what you're trying to do or what the director is trying to do —

otherwise you end up moving in two different directions. I think it's

absolutely essential to be aware of that. So when you come to a

production, confident that the director has prepared the opera well with

his opinions, ideas and interpretation, then you must immediately

double-check whether this interpretation is in conflict with what you

think is the essence of the composer's will. You have to decide if you

think it works, if it doesn't work. You try it out — maybe you're wrong,

or maybe you have an idea. You find something else and say 'How about

trying this? I know what you want, I understand the essence of your idea

but I think we can show it in a different way than you originally

intended. Then you can build on that and maybe come up with an even

better interpretation than the director's original draft—or the

conductor, same situation. I have my ideas of interpreting—of tempos,

dynamics, rallentandos, going slower here, faster there — and so has the

conductor. And we have to find a way to combine these into something

that pleases everybody.

If you're in a production with a

long run, does the interpretation change over time or are you

fine-tuning?

Of course, during the rehearsal process a

lot changes. In the beginning you think 'This is perfect, I think we

should go in that direction, and then it's 'No, I want to see more of

this. You always try to change the way you look at something and make it

more interesting, unique and satisfying. You should never stop changing

things, although there are some basics that you can't change once

opening night has arrived. You cannot, in performance number three, say

'You know what? I have a totally new idea. It came overnight...: You

have to save it for your next production because it's not fair. But what

you can and should do is be absolutely certain as to the circumstances

of your feelings, your wishes, about interpreting every thought, and

then you do it. These feelings, these situations appear to always be the

same. But if you look closer, they're very different because your life

experience constantly changes your way of seeing things and makes you do

something different, makes you understand that what you thought was

important in playing this character is not as important as some other

things that you discover. So I think you should never stop changing,

meaning I start from scratch when I open my mouth and while I

will

likely end up more or less with the interpretation I had in my head,

sometimes you find another level — a phrase that you're singing, you

give it another meaning by changing the strength, by saying it more

ironically or truthfully. These little details should always be

questioned and if they don't perfectly fit with your muse, they should

be changed.

And these changes help you achieve

spontaneity during a performance.

Absolutely—this is

what keeps the interpretation alive. It's what helps keep you fresh and

ultimately credible because it's what comes out of you in the moment and

not something the director put into your head six weeks ago.

After Parsifal and The Ring we have this idea of you now — at

least in New York —as a Wagnerian tenor. I think that's a misconception.

Because now comes this Verdi album. And it seems to me that you

ultimately have a voice that is so flexible, both dark and light. Would

you define yourself as a spinto tenor or Heldentenor or do you just work

with your voice as it evolves?

No, I would never define

myself as being a Wagner or a Verdi or a Puccini or a Mozart or whatever

tenor — tenor, yes, so far, I would say. [Laughs.] But the rest, it's

interpretation. I don't sing Wagner or Verdi or even songs with a

different voice or a different technique. I do [sing] with respect to

the different circumstances, pace and style of the music, but never with

an eye toward perfection or a habit that other people made so popular

that it became so-called 'tradition: That's a dangerous word because

tradition is something very important as long as there are reasons

behind it — reasons to support the impact of the work or to make the

audience better understand the music's intention, but not because it's

easy, let's say, to take a big gap here and a big breath because it's

not comfortable to sing it in one phrase, or to add things because there

was a colleague who started the idea of 'I want to show off.' As soon as

these things happen, as soon as you do a piano only to show the world

'even on this note I can do a piano: who cares? You can show your

friends, your teacher, and they'll be proud of you, but the audience is

not interested in that. If the audience wants to see a super-special

ability, they go to the circus or to a freak show. But in opera they

want to see something that touches their hearts, that is emotionally

overwhelming. If I do something just because I can, it doesn't make

sense.

You have been very open about some vocal problems

you had earlier In your career [circa 1995]. Why Is It taboo to talk

about vocal problems?

When I had my vocal problems,

almost everyone in the audience was aware of them — at least I had that

impression. Very often people have vocal problems but they aren't that

obvious and they can cover them up with an extra boost of energy or

enthusiasm, or with interpretation. But this is very dangerous because

if you have a problem and you change the way you sing — the way you

treat your instrument — in order to compensate for your problem, this

'compensation mode' becomes ingrained and when you're back on track,

you're singing incorrectly, at least for a healthy instrument — and you

can't get rid of these bad habits. That's why it's difficult to make the

decision to go public and say 'You might not know this, but I do have a

problem. Therefore I need to stop and I'm coming back in a couple weeks

or months.' That's very tough. As you say, I've been quite open with it,

but it's not that easy. If I say I have a cold and have to stop for a

week, it's a disaster for all the people who have tickets to these shows

and who are understandably disappointed. And if you say 'Well, I still

have it; the doctor said I should wait a couple more days: then rumors

are flying: 'He's trying to cover something up — he probably has vocal

nodules!' Then you say 'Well, even though the doctor says to wait it's

probably better that I start back earlier to prevent rumors.' So this is

a reason for people not to come out and say 'I have this problem; it'll

be over soon. Just relax.' Because then everyone panics and says 'Oh

God, we all knew it. We've seen it coming these past couple years,

totally wrong repertoire, blah blah blah.'It's an endless avalanche. So

I understand people who don't talk about it, but as soon as my body, my

instinct or my doctor tells me 'You should make the call: I do it. It

pays off at the end of the day. No one will say 'I went to hear him and

he shouldn't have sung' and your career won't end early because you

failed to take care of your voice.

You took charge of

your career in 1996. Today I have to think that, much like the former

Soviet Union, you're now on the Five Year Plan [Major opera houses plan

their productions/soloists five years in advance.] There must be a

downside here, in that you can't be so spontaneous about what you choose

to sing.

That's absolutely true. You can't change it and

I think this is ridiculous. We are artists and spontaneity is part of

our fuel. It's required to have the passion, the joy, the fun in what

you do. It's important, as it gets the fire from the audience when they

see that you're having fun yourself. If you are in the opera world it's

not like being a painter who throws away all his red paint because he

decided overnight he would use green paint now only green, no red. I

can't do that. I have to decide which colors I'm going to use for my

paintings in five years' time.

And you have to imagine

what paint is going to be available to you!

Exactly.

Which ones do I want to use and which ones will I actually have? As

you've said, the instrument is part of our body and it evolves. It

changes because you're aging, it changes with your experience in a

positive way and it changes either positively or negatively based on the

parts you've taken or not taken before those five years are over. It's

difficult and I can assure you I'm quite sick of making these decisions

from so far away. It's like you are a child, and you see the perfect toy

in front of you that would be ideal for you right now but they tell you

'Well, you've decided on all your Christmas presents until you're

eighteen. So will you want this then?' And you say 'Well, I don't know.

Maybe at sixteen I'll reconsider if I'm still into Playmobil'. So that's

tough but that's the way it is. On the other hand, with everyone fearing

for a job tomorrow, of course I'm in a luxurious situation to say that

I'll have a job in five years' time and my future is safe.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|