|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gramophone, September 2008 |

| James Inverne |

Leading light

|

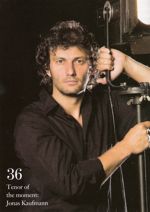

Jonas Kaufmann

Artist focus |

|

Jonas

Kaufmann not only possesses one of operas most exciting tenor voices, he

is also a terrific actor —the two are inextricably linked, he tells James

Inverne

The Kaufmann moment. For conductor Franz Welser-Möst it happened

midway through a 2003 performance of “Tannhäuser” he was conducting at the

Zurich Opera when the young German tenor stepped forward as Walther von

der Vogelweide for a brief solo. “Everybody considered him a Mozart tenor,

but suddenly I heard these notes coming out of his throat and thought,

‘Wow — this is a big voice!’ It was one of those very exciting moments.” The Kaufmann moment. For conductor Franz Welser-Möst it happened

midway through a 2003 performance of “Tannhäuser” he was conducting at the

Zurich Opera when the young German tenor stepped forward as Walther von

der Vogelweide for a brief solo. “Everybody considered him a Mozart tenor,

but suddenly I heard these notes coming out of his throat and thought,

‘Wow — this is a big voice!’ It was one of those very exciting moments.”

For me it occurred during the Flower Song in Bizet’s Carmen at Covent

Garden in December 2006 — Kaufmann’s Don José thrillingly allowing his

voice to swell and ebb as the musical line demands, suggesting all the

pent-up anguish and anger of the volatile soldier, then, astonishingly,

culminating in the most delicate (and rarely attempted) floated pianissimo

at the climactic high B flat. For Kaufmann himself, it happened when he

visited the American singing teacher Michael Rhodes, who told him to stop

trying to sound like a light, modern-day Fritz Wunderlich and to find the

darkness within the voice. Kaufmann trusted the sound that emerged and

found himself free of his vocal problems, free to concentrate less on the

technical demands of singing and more on drama and character. For Kaufmann

today, recently signed to Decca with a solo disc already in the shops and

a Carmen DVD (that Covent Garden production) about to follow, is a major

tenor of many strengths. A voice that can range from the delicacy of

Tamino to the desperation of Florestan, a charismatic, handsome stage

presence, and an intensity on stage that recalls the great vocal actors.

“He’s such a sensitive performer on stage,” enthuses the English baritone

Anthony Michaels-Moore, who in 2006 played Germont père in Kaufmann’s

Metropolitan Opera debut in La traviata. “The Germonts don’t share the

stage for very long, and certain tenors simply go into their own space

when the father is lecturing the son, but he didn’t. He gave so much just

by his expression and his body language that I had something to play off.

He listens, he reacts, so there was a real sense of shared frustration

between the two men.

For his recent Covent Garden Violetta, Anna Netrebko, his secret is that

ability to react. “He is so quick to respond on stage to what you do that

you get a sense of a history between the characters and a relationship

that they have built together.”

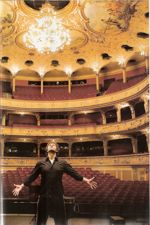

Kaufmann

himself, relaxed and talkative in an outdoor café at the Zurich Opera

House — where he has just opened in an intensively rehearsed (often until

late at night) and well received Carmen opposite Vesselina Kasarova —

traces his approach to acting back to two signal moments in his life. The

first, when he was five years old, was his first visit to the opera in his

native Munich. “We were sitting in die front row for Madama Butterfly,” he

explains, “and I was emotionally so touched when Butterfly committed

suicide, it really had a huge impact on me. But there was a still greater

impact when she reappeared 10 seconds later to bow and smile. And I

thought, ‘This can’t be!’ The illusion was destroyed and I was really

shocked. Because you take it all for real as a child, you don’t have these

shields to distance yourself. From that moment on the impact that opera

can have fascinated me.” Kaufmann

himself, relaxed and talkative in an outdoor café at the Zurich Opera

House — where he has just opened in an intensively rehearsed (often until

late at night) and well received Carmen opposite Vesselina Kasarova —

traces his approach to acting back to two signal moments in his life. The

first, when he was five years old, was his first visit to the opera in his

native Munich. “We were sitting in die front row for Madama Butterfly,” he

explains, “and I was emotionally so touched when Butterfly committed

suicide, it really had a huge impact on me. But there was a still greater

impact when she reappeared 10 seconds later to bow and smile. And I

thought, ‘This can’t be!’ The illusion was destroyed and I was really

shocked. Because you take it all for real as a child, you don’t have these

shields to distance yourself. From that moment on the impact that opera

can have fascinated me.”

The great revelation, though, came in 1997 through an unforgettable

encounter with the iconic Italian director Giorgio Strehler. Strehler had

returned to the theatre he founded, the Nuovo Piccolo Teatro in Milan,

with a sense of purpose — to bring true theatrical values back to opera

(at a time when many singers were refusing to agree to his demand for at

least six weeks of rehearsals) through the one work he had always avoided,

Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte. “He hated the fact that staging was a minor issue

for singers,” says Kaufmann, whom Strehler cast as Ferrando. “He had never

felt ready to take on Cosi and would say, ‘It is so precious, I want it to

be perfect’. So he drove us hard.”

His methods fascinated Kaufmann. “He would never give us physical stage

positioning, but concentrated on emotional positioning, trusting that to

guide our movements. He would talk through a scene, through its emotional

background, for an hour or more, until we were pleading, ‘Please, Giorgio,

let us do it!’ He would then say, ‘OK, you enter here, you exit there and

all the rest is up to you’. And you would do what you felt and he would

say, ‘Perfect! But you will feel differently tomorrow so don’t repeat what

you did today. Always make it fresh’.”

The tenor took this advice to heart, but the Così experience had a tragic

twist. “We were all planning to have some days off over Christmas ahead of

the opening. All the flights were booked and we were due to leave on

December 22. Suddenly Strehler announced that we couldn’t leave things as

they were and everyone had to work extra days. ‘We have to finish this

now, I’ll pay for the flights, but we must stay here and get this right,’

he insisted. There was a big fight, but we stayed and the cast went home

on the 24th. All this

because

he was seized by the inspiration and didn’t want to let it go. And he

finished it. And on Christmas Day he died.” because

he was seized by the inspiration and didn’t want to let it go. And he

finished it. And on Christmas Day he died.”

“The irony was that after his death, nobody knew what to do. Because

Strehler was a tyrant, who would scream at everybody but the singers. So

after he was gone, there was no one else who could take over. There was a

TV team who had filmed the rehearsals for a documentary, and the company

took the videos, watched them obsessively and then forced us to repeat

what we had done, down to the tiniest movement. It was to preserve

Strehler’s last work, but of course this was exactly what he hated! It was

very sad; we lost interest in the production and the first night was a

nightmare. Eventually, after the first two, three weeks, the cast started

to find their interest again and slowly but surely rediscovered the

lessons Strehler had taught us. We followed his ideas again, finding our

freedom on stage and by the end of the run it was wonderful. I learnt so

much about what to do and what not to do during that production.”

The Strehler experience came as the 28-year-old tenor was struggling to

find his way. Three years earlier, while he was under contract to the

Saarbrücken Opera, he had lost his voice on stage (“I pray that never

happens again,” he says, a loot of real fear in his eyes). It was then

that he met Rhodes, emerging from his lessons with the beginnings of a

darker, weightier voice. But he had to leave Saarbrücken. “I was singing

Rossini and Donizetti there and needed to exercise the voice in its new

form,” he recalls. So — after an attempt at Don Giovanni’s Ottavio, which

he admits to having been “disgusting, awful” — he left and faced the

world, jobless, knowing that his voice was no longer the one for which his

repertoire had previously been shaped but not yet sure where it was going.

“It was a leap into the darkness,” he says, “not only with the career but

with the voice itself. The process was ongoing. I was at last confident

that I could handle my voice and was secure in using it, but it was not

the sound I have now. Yet from the moment I freed my voice I left it in

peace. I never tried to force it to do what it was not meant to do. So it

began to grow and darken, and I could understand more and more as time

went on where it wanted to go.”

Given the voice’s similarities to Ramón Vinay and, to a lesser extent, Jon

Vickers, I ask whether he had any models for its development. Kaufmann is

emphatic. “No. As soon as I realised what I had been doing before I met

Michael, trying to imitate and manipulate, I tried to avoid sounding like

anybody. I even practised with my hands over my ears sometimes, to truly

let the voice go where it wanted. Of course, now I do see parallels with

Vinay and also with Plácido Domingo, and Plácido sings German and French

repertoire

alongside

Italian, which is something I’m also trying to do, so there may be extra

similarities.” alongside

Italian, which is something I’m also trying to do, so there may be extra

similarities.”

Both those singers started as baritones — Vinay went back there and

Domingo is about to follow suit. I wonder if the trick to flexibility of

repertoire is not heft (neither Domingo nor Kaufmann have especially thick

voices) but a very firm, low centre to the voice. There is, with Domingo,

a sense of a voice firmly set in its shape and anchored. “It’s vital to

have a centre,” agrees Kaufmann. “When I was younger I greatly admired

Pavarotti for his high notes. They seemed to be so effortless and so

strong. But also he sang those high notes at a cost to other parts of his

voice. That is a very Italian way of thinking, that the high notes must be

great at any cost. If I can’t reach those notes from where I stand I won’t

try and stretch. Everybody kept saying, ‘No, you must slim the voice down

as it ascends; if you don’t thin out the voice at the top you will never

reach the high notes’. But if you try to close everything off like that it

will never reopen in the same way.”

As his career rebuilt, audition by audition, engagement by engagement,

Kaufmann learnt another lesson. “I am in the fortunate position that many

houses want to engage me all over the world. But it is not healthy for the

voice to be always travelling. I am a family man, I have a wife and

children, and it is important to the artist as well as the man to spend

time with them.”

Still, easy to preach, less easy to practise in a world crying out for

top-class dramatic tenors and are there others of his generation who can

approach Kaufmann’s range of repertoire? Roles stretch from Wagner’s

Parsifal to Verdi’s Alfredo, from Beethoven’s Florestan to Massenet’s Des

Grieux, and the next few years will see him add heavier parts - Berlioz’s

Aeneas and Wagner’s Siegmund - and lighter fare such as Massenet’s

Werther. One of the few who understands and shares his dilemma is that

other contender for Domingo’s crown, Rolando Villazón. The Mexican at

present may have a timbre much more akin to his mentor’s than has

Kaufmann, but it is the German who can boast the wider span. Despite any

perceived rivalry we journalists are likely to whip up, though, the two

men are friendly and even share problems. “It was funny recently, because

my wife said to me, ‘Next time you see Rolando, ask him how he manages

everything with the career and the children’. I saw him the next morning,

and he says, ‘Oh Jonas, my wife told me to ask you how you manage

everything with the career and the children!”’

“Everything” for Kaufmann means a lot, not only opera but song as well.

Last year his disc of Richard Strauss songs won a Gramophone Award and he

is keen to explore more of this territory. “Strauss in particular

fascinates me,” he says, “Early on, I had some lessons with Hans Hotter,

who knew Strauss well and would show me not only how Strauss wanted

something to go but the kind of character he was. He told me about how

Strauss would have screaming rows with his wife that would last for hours

and then Strauss would sit down and write the most amazing love song. Out

of this terribly difficult moment would emerge something of incredible

beauty. It has a great effect on the way you

perform

these songs after hearing that.” perform

these songs after hearing that.”

For now, though, opera is uppermost in his mind, Don José the character of

the moment. I point out that it has become a cliché of opera reviews to

admiringly refer to the tenor as so good that “the opera could have been

called Don José” and wonder whether José is in fact a more grateful part

than Carmen herself. “He goes on more of a journey,” Kaufmann agrees. “The

problem for Carmen is that she stays much the same from beginning to end

and it is very difficult to show more complexity to her. Whereas with José

you have such a development in the character.”

But, by the same token, isn’t José’s journey always the same? “Not at all.

In the London production we were doing the version with dialogue, where

José mentions that he is a murderer. He has already, whether by accident

or in a fight, killed somebody and is now starting a second life in the

military. So this shows me that on the one hand he wants to fit in and

assimilate with the others, but on the other hand he is a ruffian given to

frightening over-reactions. So in London, I tried even from the beginning

to show that something is wrong with this guy, and seeing these two

outsiders —Carmen and Don José — come together you know that it must end

badly.”

“What we did here in Zurich was the version with recitatives, where there

is almost no talk of his life before. The only thing you hear is in José’s

duet with Micaëla where she says that his mother forgives him — but for

what? You never find out. Maybe it is simply the fact of him leaving home

rather than staying in the village and marrying Micaëla. This gives the

opportunity to show a completely different character, and what I did here

was to show someone who was very brave, but also a perfectionist. He has

probably never had sex, and lives in his own little ordered world — his

shirt always tucked in, his uniform beautifully ironed and his hair as if

mummy has cut it. Suddenly Carmen destroys him by showing him what life

could be, all these possibilities he has never considered and he’s utterly

obsessed by her.”

That Kaufmann takes the drama seriously is clear by his process of

studying a new role — he studies all the characters, not merely his own.

“You get many clues to your character from what others say about you. And

not just that — your character can be partly created by the way he appears

in contrast to the others. All characters should not be equal, that would

be uninteresting. So you must know the others to understand how yours

should fit into that framework”

As

the heavier parts line up to join the Kaufmann repertoire, one looms

larger than most — and one which he has so far avoided —Verdi’s Otello. He

made his Chicago debut in 2001 as Cassio and must, I suggest, have been

dying to swap parts. He laughs. “I’m extremely eager to do this part. The

problem now is not the vocal difficulties but the character. It really

drives you mad on stage, it’s so all-consuming. There must be the last

vestige of rational control, otherwise you can really hurt your voice. As

the heavier parts line up to join the Kaufmann repertoire, one looms

larger than most — and one which he has so far avoided —Verdi’s Otello. He

made his Chicago debut in 2001 as Cassio and must, I suggest, have been

dying to swap parts. He laughs. “I’m extremely eager to do this part. The

problem now is not the vocal difficulties but the character. It really

drives you mad on stage, it’s so all-consuming. There must be the last

vestige of rational control, otherwise you can really hurt your voice.

His commitment is confirmed by his Carmen co-star Anna Caterina Antonacci:

“He really went through that intense last act without any limits — he

takes risks, even taking the voice apart.” But Kaufmann is taking this one

sensibly, step by step. First, perhaps, the Act 1 duet in concert with

Renée Fleming this year, then a full concert at some point. “I’m

absolutely sure I will sing Otello though,” he adds. “It’s what allows me

to be patient. If I had any doubt I would have done it already.” He looks

determined.

(Carmen is released on DVD by Decca in September; Jonas Kaufmann’s solo

album “Romantic Arias” (4/08) is also on Decca) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|