|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

El Mercurio, 5.9.2015 |

| Por Juan Antonio Muñoz H. |

|

|

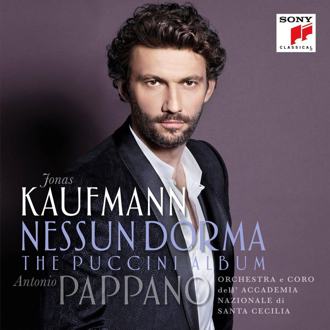

JONAS KAUFMANN EN PUCCINI: PASIONES EXPLOSIVAS E INSOMNIO

GARANTIZADO

|

|

“Nessun

dorma” (Sony, 2015), el notable nuevo álbum de Jonas Kaufmann, se

desenvuelve en al menos tres sentidos. Estos son que la música de Puccini

está compuesta para el teatro, que hay una evolución en su forma de componer

para la voz y que un artista de verdad —como lo es el tenor bávaro— puede

actualizar la concepción interpretativa siendo fiel al estilo. “Nessun

dorma” (Sony, 2015), el notable nuevo álbum de Jonas Kaufmann, se

desenvuelve en al menos tres sentidos. Estos son que la música de Puccini

está compuesta para el teatro, que hay una evolución en su forma de componer

para la voz y que un artista de verdad —como lo es el tenor bávaro— puede

actualizar la concepción interpretativa siendo fiel al estilo.

Aquí

estamos ante un Jonas Kaufmann que abruma con su voz oscura y abaritonada,

de agudos resplandecientes, ofreciendo un canto generoso y noble. Un

cantante para el cual la voz es vehículo de una personalidad escénica

enorme, que asume en cada frase el peso de la dramaturgia, al punto de ir

más allá de las convenciones operísticas. Es como si hubiera hecho carne las

palabras que un ya mayor Giacomo Puccini escribió a un amigo: “Dios

Todopoderoso me tocó con su dedo meñique y me dijo: ‘Escribe para el teatro,

recuérdalo, solo para el teatro’, y yo he obedecido el mandato supremo”.

Por cierto, Kaufmann podría actuar sin cantar, y ese magnetismo de su

implicancia dramática se siente a través del disco. La voz está expuesta

aquí, además, de manera dispendiosa, pero, curiosamente, jamás con alarde,

porque prima una preocupación por los matices y por los detalles: es su

formación en el mundo de Lied aplicada a Puccini. Un Puccini en el que se

descubre la atención a la scapigliatura, al mundo verista, a la herencia del

belcanto expandida por Verdi e incluso al melodismo francés.

Todo

esto porque el álbum —lujoso, disponible en CD y vinilo, y que cuenta con la

dirección de Antonio Pappano, probablemente el mejor director de ópera

italiana de la actualidad, al frente de la orquesta y el coro de la

Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia—, hace un viaje no cronológico por

todos los títulos de Puccini, desde la temprana “Le Villi” (1884) a la

póstuma “Turandot” (estreno en 1926). Kaufmann se abstiene de cantar “Suor

Angelica”, por razones obvias.

Los cuatro primeros tracks están

dedicados a “Manon Lescaut” (1893) y su Renato des Grieux. Abre con un

ensoñado “Donna non vidi mai”, donde la ilusión por la amada recién conocida

se devela en palabras como “carezzare” o “susurro gentil”; luego sigue el

dúo del segundo acto (con una sensible y acalorada Kristine Opolais), donde

viene la explosión de las pasiones, con las recriminaciones de “O

tentatrice” (Oh, tentadora), la lamentación de “Più non posso lottar” (No

puedo luchar más), el triunfo de la satisfacción erótica en “Nel l’occhio

tuo profondo io leggo il mio destin” (frase que resiste muchas

interpretaciones y que puede traducirse como “En lo profundo de tus ojos leo

mi destino”) y hasta el ahogo postcoital de “Dolcissimo soffrir” (“dulcísimo

sufrir”, guiño a la “pequeña muerte” o a la “dulce muerte”). Kaufmann canta

el deseo desde un punto aristocrático y avanza luego a la rabia de Des

Grieux en “Ah Manon, mi tradisce il tuo folle pensier” (¡Ah! Manon, me

traicionan tus locos pensamientos) y la imposibilidad de escapar: “Io? Tuo

schiavo e tua vittima discendo la scala dell’infamia” (¿Yo? Tu esclavo y tu

víctima desciendo por la escalera de la infamia). Termina con la gran escena

de Des Grieux del tercer acto, “Ah! Non v’avvicinate”, con la declamación

vehemente, la candidez de la imploración y el climático Si que desarma a

cualquiera.

Ya en ese último fragmento nos encontramos con un canto

que viaja entre la declamación de un discurso y el lirismo de un aria, lo

que define el enfoque vocal de Puccini para “Le Villi” y “Edgar”. Kaufmann

convierte “Torna ai felice dì”, de la primera, en una escena de nostalgia

acicateada en todo momento por el terror. En el caso de “Edgar” (1889),

“Orgia, chimera dall’occhio vitreo... O soave vision” es ejemplo de música

amplia y expansiva, vigorizada con el estilo declamatorio propio del verismo

y —vaya mezcla— con clara influencia del Massenet de “Herodiade” (“Vision

fugitive”). Rodolfo de “La Bohème” (1896), que fue un personaje importante

para Kaufmann en sus años en Zúrich, hoy no es un rol exactamente para él,

por el camino propio de su voz, pero es notable cómo acomete “O soave

fanciulla” junto a la cuidadosa Mimi de Opolais, derretida ante frases como

“Sarebbe dolce restar qui. C’è freddo fuori” (Sería tan dulce quedarse aquí.

Hace frío afuera) o ante la pregunta insinuante “E al ritorno?” (¿Y a la

vuelta?). “Tosca” (1900) —el Cavaradossi de Kaufmann es de manual— está

representada por “Recondita armonia”, que viene con el “perdiéndose” del

conclusivo “Sei tu”, que casi nadie respeta. En “Madama Butterfly” (1904),

el tenor casi hace olvidar la materia de la que está hecho el despreciable

Pinkerton y borda con emoción su “Addio fiorito asil”.

Rol magnífico

para Kaufmann es Ramerrez/Johnson de “La Fanciulla del West” (1910), que

canta “Una parola sola” con una intensidad descomunal que electriza y excita

en “la mia vergogna” (mi vergüenza); acto seguido hace de “Ch’ella mi creda

libero e lontano” una plegaria filorreligiosa. Además, las revelaciones que

Pappano desprende de la poderosa escritura orquestal son sorprendentes. “La

Rondine” (1917) ofrece un intermedio lúdico con “Parigi è la citta dei

desideri” para ir a los brazos rudos de Michele de “Il Tabarro” (1918), un

papel que el tenor aún no canta en vivo y en el que estaría perfecto: su

“Hai ben raggione” tiene toda la rabia del grito proletario de

insatisfacción y resentimiento que vive tras las palabras “mejor no pensar,

bajar la cabeza y encorvar la espalda”. Uno piensa qué podría hacer el

barítono del rol titular de “Gianni Schichi” (1918) si sale un tenor que

canta el adolescente Rinuccio como lo hace Kaufmann. Por cierto, no es papel

para él, pero qué voz tan magnífica para exaltar Florencia, el Giotto y el

Arno. Es como darse un gusto. Kaufmann se lo da a sí mismo y también a los

auditores.

Resta lo más esperado: su Calaf de “Turandot”. Si la

pequeña Liù había quedado prendada del príncipe solo por una sonrisa, tras

este “Non piangere, Liù” (No llores, Liù), cantado con una dulzura

inconmensurable, ella no tiene escapatoria: tendrá que suicidarse por amor.

Y su “Nessun dorma” —pleno de colores desde las sombras a la luz—, con el

que hizo temblar a la Scala de Milán el 14 de junio pasado, no permitirá que

nadie duerma por un buen rato. Por supuesto, la misántropa princesa

Turandot, turbada, no podrá dormir más y dejará caer su velo de plata una y

mil veces, y con todo gusto.

JONAS KAUFMANN IN PUCCINI: EXPLOSIVE

PASSIONS AND GUARANTEED INSOMNIA

Juan Antonio Muñoz H.

“Nessun dorma” (Sony, 2015), the remarkable new album of Jonas Kaufmann,

unfolds in at least three senses. These are that Puccini’s music is composed

for the theater, that there is an evolution in his way of composing and that

a true artist —like the Bavarian tenor— can update the interpretative

conception, remaining true to the style.

Here we are before a Jonas

Kaufmann that overwhelms us with his dark and baritone-like voice, with

sparkling high notes, offering a generous and noble song. A singer for whom

the voice is the vehicle of a huge scenic personality, who assumes in each

phrase the weight of the drama, to the point of going beyond operatic

conventions. It’s as if he had embodied the words that an already ageing

Giacomo Puccini wrote to a friend: “God Almighty touched me with his little

finger and told me: ‘Write for the theater, remember, only for the theater’,

and I have obeyed the supreme mandate”.

Kaufmann could certainly act

without singing, and that magnetism of his dramatic implication is felt

throughout the record. The voice is also exposed in a wasteful manner but,

strange to say, never boastfully, because his main concern is for nuance and

detail: it’s his training in the world of the Lied applied to Puccini. A

Puccini in which we discover the attention to scapigliatura, to the Verdian

world, to the heritage of the belcanto expanded by Verdi and even to French

melodicism.

All of this because the album —lavish, available on CD

and vinyl, with Antonio Pappano, probably the best Italian opera conductor

today, conducting the orchestra and choir of the Accademia Nazionale di

Santa Cecilia—, makes a non-chronological tour of all Puccini titles, from

the early “Le Villi” (1884) to the posthumous “Turandot” (debut in 1926).

Kaufmann refrains from singing “Suor Angelica”, for obvious reasons.

The first four tracks are dedicated to “Manon Lescaut” (1893) and its Renato

des Grieux. It opens with a dreamlike “Donna non vidi mai”, in which the

illusion for the recently met loved one unfolds in words such as “carezzare”

or “susurro gentil”; next is the duet from the second act (with a sensitive

and heated Kristine Opolais), with the explosion of passions, the

recriminations of “O tentatrice” (Oh, temptress), the laments of “Più non

posso lottar” (I can fight no more), the triumph of erotic satisfaction of

“Nel l’occhio tuo profondo io leggo il mio destin” (a phrase that resists

many interpretations and can be translated as “In the depth of your eyes I

can read my destiny”) and up to the post-coital choking of “Dolcissimo

soffrir” (“Sweetest suffering”, a wink to the “small death” or to the “sweet

death”). Kaufmann sings desire from an aristocratic point and then

progresses to the anger of Des Grieux in “Ah Manon, mi tradisce il tuo folle

pensier” (¡Ah! Manon, your crazy thoughts betray me) and the impossibility

of fleeing: “Io? Tuo schiavo e tua vittima discendo la scala dell’infamia”

(I? Your slave and victim descend the stairs of infamy). It ends with the

great scene of Des Grieux in the third act, “Ah! Non v’avvicinate”, with the

vehement declamation, the candor of supplication and the climatic B (Si)

that disarms everybody.

Already in that last fragment we find a song

that travels between the declamation of a speech and the lyricism of an

aria, which defines the vocal focus of Puccini for “Le Villi” and “Edgar”.

Kaufmann turns “Torna ai felice dì”, from the first one, into a scene of

nostalgia spurred at all times by terror. In the case of “Edgar” (1889),

“Orgia, chimera dall’occhio vitreo... O soave vision” it is an example of

broad and expansive music, invigorated by the declamatory Verdian style and

—what a mixture— with clear influence of the Massenet of “Herodiade”

(“Vision fugitive”). Rodolfo of “La Bohème” (1896), who was an important

character for Kaufmann during his years in Zurich, is nowadays not a role

cut out for him, due to the path his voice has taken, but it is remarkable

how he undertakes “O soave fanciulla” beside the cautious Mimi of Opolais,

melting in phrases such as “Sarebbe dolce restar qui. C’è freddo fuori” (It

would be nice if we could stay here. It’s cold outside) or with the

insinuating question “E al ritorno?” (And when we return?). “Tosca” (1900)

—Kaufmann’s Cavaradossi is textbook— is represented by “Recondita armonia”,

which comes with the “losing himself” of the conclusive “Sei tu”, which

almost nobody respects. In “Madama Butterfly” (1904), the tenor almost makes

us forget the material of which is made the despicable Pinkerton and he

addresses with emotion his “Addio fiorito asil”.

A magnificent role

for Kaufmann is Ramerrez/Johnson of “La Fanciulla del West” (1910), who

sings “Una parola sola” with an enormous intensity that electrifies and

excites us in “la mia vergogna” (my shame); he then turns “Ch’ella mi creda

libero e lontano” into an almost religious prayer. Moreover, the revelations

that Pappano deducts from the powerful orchestral score are surprising. “La

Rondine” (1917) offers a playful interlude with “Parigi è la citta dei

desideri” to then go to the tough arms of Michele in “Il Tabarro” (1918), a

role that the tenor has not yet sung on stage and in which he would be

perfect: his “Hai ben raggione” has all the anger of the proletarian cry of

dissatisfaction and resentment he experiences after the words “it is best

not to think, to bow your head and bend back”. One wonders what the baritone

of the leading role of “Gianni Schichi” (1918) could do faced with a tenor

who sings the part of the adolescent Rinuccio as Kaufmann does. It is

certainly not a role for him, but what a magnificent voice to exalt

Florence, Giotto and the Arno! It’s like a treat. Kaufmann gives it to

himself and also to the public.

The most expected thing remains to be

heard: his Calaf of “Turandot”. If little Liù fell in love with the prince

with just a smile, after this “Non piangere, Liù” (Don’t cry, Liù), sung

with an immeasurable sweetness, there’s no escape for her: she will have to

kill herself for love. And his “Nessun dorma” —full of colors from shadows

to light—, with which he made the Scala of Milan tremble in June 14 of last

year, will not allow anyone to sleep for quite some time. Naturally, the

misanthropic princess Turandot, distraught, will not be able to sleep

anymore and will let drop her silver veil one and a thousand times, and

gladly.

Juan Antonio Muñoz H.

Editor of Espectáculos & Vidactual

EL MERCURIO SAP

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|