|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| classicalsource.com |

| Richard Nicholson |

|

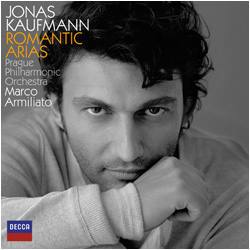

Jonas Kaufmann – Romantic Arias

|

|

|

This

is the second Jonas Kaufmann recording that I have heard. The first, for

Harmonia Mundi, of Richard Strauss Lieder, issued in 2006, was a rewarding

experience, Kaufmann managing his voice through a diverse range of

challenges, impersonations and vocal acting that brought out the genius of

Strauss’s settings as few others have done in the studio. That glittering

achievement whetted the appetite for more, especially in the operatic field. This

is the second Jonas Kaufmann recording that I have heard. The first, for

Harmonia Mundi, of Richard Strauss Lieder, issued in 2006, was a rewarding

experience, Kaufmann managing his voice through a diverse range of

challenges, impersonations and vocal acting that brought out the genius of

Strauss’s settings as few others have done in the studio. That glittering

achievement whetted the appetite for more, especially in the operatic field.

Kaufmann has since drawn enthusiastic reviews for operatic roles and now

ventures into the inevitable recital release. The title “Romantic Arias”

raises questions when considered alongside the wide-ranging repertoire

included and the marketing material that accompanied this issue. Decca is

attempting to establish as this singer’s Unique Selling Point that he is

equally at home in music from Mozart to Wagner. The selections do not

include anything by Mozart and the Wagner role represented here is that of

Walther von Stolzing, the lightest leading-tenor part in the Wagner canon.

What is intended by the term “Romantic”? Does it refer to the European

literary movement that advocated the free release of strong emotion and

prized raw nature, the musical style of post-Beethoven composers or simply

to the general connotations of the word with a lower-case ‘r’ as concerned

with love?

The latter is almost confirmed by the choice of arias, though ‘Nature

immense’ from “La damnation de Faust” is neither an operatic aria nor a

love-song. That piece is arch-Romantic in terms of the singer’s exaltation

in the presence of nature, as well as in the use of the orchestra. So

arguably it is the only track on the recording that fulfils my three

criteria. And mightily impressive it is from Kaufmann. He sustains the long

phrases with assurance, responds to Berlioz’s constantly shifting harmonies

with exemplary musicianship and delivers the monumental waves of power with

flashing, heroic tone.

There is little except the theme of love to connect some of the other

selections. The light romanticism of theme and style in Flotow’s “Martha” is

a world away from the heightened emotion of verismo: Kaufmann’s treatment of

the coda of ‘Ach so fromm’ is far too muscular for the role of Lyonel in

this gentle comedy. Romanticism in Weber’s “Der Freischütz” means something

different again, a mixture of soft sentiment and the threat of the

supernatural. These alternate in Max’s Scene. Biting anger in the pungent

enunciation of the opening recitative gives way to fluid tone in the aria,

with a hint of Fritz Wunderlich’s style in some of the top notes, convincing

terror in the bridge passage, tenderness at the vision of Agathe and the

deployment of the heroic potential of the voice to represent the character’s

despair in the final allegro. This is a great performance of a great aria.

It is to the singer and conductor’s credit that they make one feel that

Faust’s aria from Gounod’s opera also deserves such an epithet. The slow

tempo for the canonic string entries sets the scene for Faust’s nervous

appearance and enraptured opening to the aria. This wonderment is something

that never leaves him throughout. How many tenors concern themselves with

the response of the character in this piece, rather than displaying their

own vocal prowess? The violin solo pursues its winding course with the

singer throughout and has its own spot-lit ending after the tenor’s top C,

delivered in an impeccable voix mixte.

The other excursions into the French repertoire require a blend of lyricism

and impassioned declamation. In Don José’s ‘Flower Song’ from Bizet’s

“Carmen” there is plenty of power for the surge of emotional pressure in the

section beginning “Puis je m’accusais de blasphème” but equally the control

for the difficult ascent to the top B flat in head voice. In the Massenet

pieces Kaufmann displays the same combination of facilities. The media

frenzy devoted to seeking the “fourth tenor” as “The Three Tenors”

phenomenon wound down through the 1990s may have kept classical vocal music

in the eye of the general public but it can arguably be said to have damaged

the career of Roberto Alagna, whose attempt to push his voice beyond its

natural shape and size led to his virtual eclipse. One hopes that something

similar may not be threatening the career of Rolando Villazón. Kaufmann

appears to have the weight of voice to bisect a powerful orchestra along

with the ability and the willingness to draw in his horns.

I have to say that I do not find the voice beautiful in itself. Those who

are looking for the tonal purity of Pavarotti in his prime or the visceral

vibrancy of Franco Corelli will, if they hear the voice as I do, experience

some disappointment. A better comparison would be with Plácido Domingo,

whose intelligence, artistry and versatility resulted in a total experience

far greater than the sound of the voice. Even the Spanish tenor, however,

with his wide repertoire and constant exploration of new roles, did not

essay the breadth of music that Kaufmann does here.

These arias have been newly studied for this recorded collection. None

receives a routine performance. In the two by Puccini Kaufmann recognises

that they each contain downbeat conversational elements among the bursts of

lyricism and passion. In the aria from Act Three of “Tosca” he is withdrawn

in the opening lines, immersed in trying to bring the vision of past

happiness into focus. When Cavaradossi reaches his first lyrical phrases (“O

dolci baci, o languide carezze”), Kaufmann eschews the gorgeous honeyed

spot-lit mezza voce in which most tenors wallow, preferring instead a rather

dry sound and a restrained delivery, re-enacting the catch-in-throat of his

response to Tosca herself which is more erotic than a conventional

performance and avoids overshadowing the climax, in which the painter

bemoans his loss as he faces execution.

The hackneyed ‘Che gelida manina’ (“La bohème”) has been calculated from a

dramatic point of view and delivered in accordance with its theatrical

logic. This Rodolfo realises that Mimi’s attention is wandering in the

humdrum opening lines and that he needs to hold her back as she tries to

withdraw her hand; “Aspetti signorina” has a real urgency. Accordingly he is

really inspired in his life story; from “per sogni e per chimere” he

initiates a long controlled crescendo leading up to the big tune, never

relaxing the tension. The top C is the first example on this issue of the

heady freedom in the high register that will surely ensure the singer’s star

status. The gradual decrescendo that follows rounds off the structure

convincingly.

Middle-period Verdi, in the shape of Alfredo’s cavatina (“La traviata”,

requires a lighter touch. Again, attention to detail in the recitative

distinguishes this performance from run-of-the-mill rivals. The tone fills

with love as he reflects on the sacrifice Violetta has made for him,

starting at the phrase “Qui presso a lei…” and continuing to the end, so

that the aria emerges as a natural consequence. He does not overdo the

climax of the aria, leaving that musically for the normally omitted

cabaletta “O mio rimorso”, with its (interpolated) ringing top C. It is a

pity that he smudges the semiquavers.

The fearsome Act Two solo from “Rigoletto” has an arioso which perfectly

exploits Kaufmann’s dual strengths. The Duke is at once ruthless and loving.

The paradox of his nature is caught as by few other recorded singers. The

bite in Kaufmann’s tone for the vengeful utterances still leaves room for

the lines about Gilda to receive the caresses of a perennially sweet sound.

The aria itself, this time without cabaletta, eloquently relates the Duke’s

regret and guilt at not having been able to protect Gilda; no wonder she

fell for him!

Marco Armiliato is determined to make his mark and some details shed an

interesting light upon the orchestral writing, for example the slightly

elongated opening notes of the three repetitions on the oboe of the ‘Fate’

theme which begin the introduction to Don José’s ‘Flower Song’. I find some

details tiresome, however. ‘Ach so fromm’ has a cloying introduction and an

ineptly thunderous conclusion with reverberant thrashing of the bass drum

loading the music with weight which its relatively light frame cannot bear.

The recording tends to be over-loud in any case.

An auspicious operatic recital debut, then, from a tenor with considerable

gifts. The promotion based on his smoky good looks is off-putting, but will

not matter if he maintains his present standard of artistry. The booklet

includes texts and translations. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|