|

Jonas Kaufmann impresses with his finely judged

phrasing, psychological acuity and seductive swagger

|

|

|

|

|

|

El Mercurio |

| Juan Antonio Muñoz H. |

|

|

|

The culture of pleasure in the voice of Jonas Kaufmann |

|

|

|

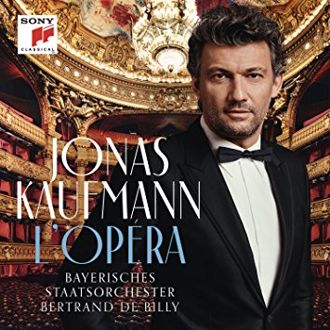

It is “L’Opéra” (Sony), a record completely dedicated to the French

repertoire, which will surely become another bestseller of the artist. |

|

|

It is for some reason that this album begins with the scene of

the young Montague lover in “Roméo et Juliette” (Gounod). It

includes the previous recitative, which begins with the words

“L’amour” (Love), and the lyrical speaker then goes on to say

that that love has disturbed his whole being. Jonas Kaufmann

offers in “L’Opéra” a song to thedeep bond he feels and

experiences for the French repertoire, but at the same time, for

love, exposed in a myriad of situations, from adolescence to the

love of a father (“La Juive”), friendship (Les pêcheurs de

perles”), desire (“Les contes d’Hoffmann”), affective doubts and

sexual intoxication (“Manon”), tenderness (“Mignon”), charm (“Le

Roi d’Ys”), religious reverence (“Le Cid”), disappointment

(“Werther” and “Carmen”), the power of Nature (“L’africaine”),

finding the ideal (“La damnation de Faust”) and facing the

inconvenient mandate of the gods (“Les troyens”).

Just

like Roméo waits for the sun to rise, the prelude to the aria

turns out to be the anteroom to listen to the voice of the great

German tenor: one waits for dawn, in a vigil, as one waits for

Kaufmann.

It is amazing that the best current interpreter

of the Gallic repertoire should be German. Jonas Kaufmann

dominates the language and the way in which it builds the

singing. His is not an approximate application, but a

deep-rooted one, exact, rigorous, which can be seen throughout

his long experience in roles such as Des Grieux, Faust (Gounod

and Berlioz), Werther and Don José, and also in his approaches

to the mélodie française, with Henri Duparc making the

experience of reading Baudelaire, Gautier and Leconte de Lisle

even more intense. Listening to Kaufmann singing “L’invitation

au voyage” or “La vie antérieure” is having access to greater

knowledge.

In “L’Opéra”, what is obvious right from the

start is that we are faced with a tenor at the top of his

expressive faculties articulating each word with precision,

taking care of the way in which the vocals assume different

positions and colors, according to the word they inhabit. An

artist fully conscious of the music he has before him and who

pursues an interpretative purpose. In other words, an artist who

knows what his ideal is and who is capable of achieving and

materializing it. In Kaufmann’s genius there beats a culture

which, to a certain extent, he has assumed as his own: the

culture of pleasure, of which France knows so much, and that is

applied in this album both to the intellectual taste for singing

these works —and this poetry— as well as to what pleasure means,

even physical pleasure.

If one listens to his “Ah

lève-toi, soleil”, Roméo certainly does not sound like a

teenager as one could expect from Alfredo Kraus or Alain Vanzo;

Kaufmann does not pretend to make us forget the baritonal seal

of his voice but uses and exposes it to delve into the anguish

of the character,the tension of waiting, Eros and the amorous

belief —lethal and adult— of a soul willing to succumb. It is

valuable to have his version, regardless of the fact that it is

unlikely that at this point he will ever sing the whole role;

something similar happens with Juliette’s waltz, once recorded

by Maria Callas, when she had already sung various “Toscas” and

“Normas”.

The same thing happens with the duet of “Les

pêcheurs de perles”, where his Nadir competes with the low tones

of the great Ludovic Tézier as Zurga. Here the seductive power

of the voices goes beyond tradition —what is expected, what is

usual— to another order so that the listener may enjoy himself

without encumbrances. We will certainly not have any

Nadir-Kaufmann in the future, but will very probably have

Samson-Kaufmann orPelléas-Kaufmann.

Another peculiarity

of this record is that it does not get to the arias directly;

they all come with their recitative, which provides the context

in which each aria develops. These are moments in which the

tenor has always something to say, such as the question

involving the word “Traduire” in “Werther”, shortly before the

character decrees that it is the poet (Ossian) who interprets

—translates— him. His new versionof “Pourquoi me réveiller” is

more tormented and desperate, almost furious, as if Goethe’s

hero could become a dangerous being. Threatening like Don José

in his obsession: that is why here the first phrase is the

imperative “Je le veux! Carmen, tu m’entendras” while “La fleur

que tu m’avais jetée”, embroidered by Kaufmann to the smallest

detail, is both a declaration of love and a cathartic

self-review.

Wilhelm Meister of “Mignon” (Thomas)

connects the tenor, again, with a character from Goethe; this

is, in addition, to poetry of German origin. His “Elle ne

croyait pas, dans sa candeur naïve” is made for his line of

singing and represents the moment of greatest tenderness of

thealbum; the aria is built on a color of painful and

languishing radiation, while for Mylio in “Vainement, ma

bien-aimée” (“Le Roi d’Ys”, Lalo), he chooses lightness and

softness, preceded by a confident “Puisqu’on ne peut fléchir…”.

One has to listen to him saying “Comme un concert divin ta voix

m’a penétre” (Like a divine concert your voice has penetrated

me) in the brief fragment chosen from “Les contes d’Hoffmann”

(Offenbach), with love needing and provoking physical

explanation.

Vasco de Gama brings the astonished

contemplation of the natural world with “Pays merveilleux… Ô

paradis” (“L’africaine”, Meyerbeer). Then Massenet andhis

“Manon” provide two great moments for Kaufmann, on this occasion

with the exquisite soprano Sonya Yoncheva. We have Des Grieux in

the almost virginal outburst of the beginning, with his sincere

and naive confessions, dreaming of the little house in the

forest where he will live his love (“En fermant les yeux, je

vois là-bas”), and later on the disappointed man, who has become

an abbot and once more succumbs, not without pain, to seduction,

although he loudly proclaims that finally “(Manon) has left my

memory and my heart” (“Toi ! Vous ! N’est-ce plus ma main”).

Kaufmann responds to the great reconquering of the woman by

giving in to voluptuosity almost with rage. Remarkable.

The recitative “Ah ! tout est bien fini”, of “Le Cid”

(Massenet), with the abandonment of the hero’s dreams of glory,

precede that prism of interpretative details that is his “Ô

souverain, ô juge, ô père”, the contained prayer of Rodrigue, a

role he should sing in full once, the same as the role of

Éléazar, of “La Juive” (Halévy), of enormous dramatic power,

with this (adoptive) father crying over the fate that awaits his

daughter. One should note what Kaufmann does with the word “moi”

in the last repetition of the phrase “(…) et c’est moi qui te

livre au bourreau”. There is no better Faust (Berlioz and once

more Goethe) than the German tenor; the inspired “Merci, doux

crépuscule” —with the mystery of the natural world lighting up

the place, the “secret sanctuary”, where love will be possible—

can only be sung by someone who dominates the greatest

subtleties of singing.

It all ends with the magnificent

scene of Énée from “Les troyens” (Berlioz), “Inutiles regrets!”,

which is a tour de force in itself, made so that Jonas Kaufmann

may splurge his vocal authority and expressive nobility, tracing

all the contours of a hero’s profile that is both lover and

warrior and who must give in to the divine requirements, that

turn out to be precisely as inhuman as the demanded aria.

Apart from soprano Sonya Yoncheva and baritone Ludovic

Tézier, he is accompanied in this label prowess by the

Bayerisches Staatsorchester, conducted by Bertrand de Billy,

current conductor of the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSO

Wien).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|