|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| El Mercurio |

| Juan Antonio Muñoz H. |

|

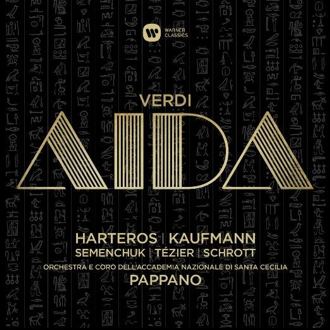

Pappano’s extraordinary “Aida”: Radames, Radames, Radames !

|

|

Leading

the choir and orchestra of l’Accademia Nazionale Santa Cecilia, which he

conducts since 2005, Antonio Pappano creates a sound space without frontiers

where voices can live in intimacy and also in midst of the masses (few

operas have as many “asides” as this one), thus accepting the difficult

mixture proposed by the score which is so hard to balance. His conduction

enthralls us with the colorful encounters, the haziness, the internal

vibration and constant unrest of the atmosphere. If the scene at the Temple

of Vulcan —extremely well accomplished— puts all this together in the

contrasting levels of heroism and prayers, the preludes to Acts I and III

lead us to an iridescent musical environment that takes us through

undulating roads towards sensuality, mysticism and human passions that here

come into play, both frantic and subterranean. The building constructed by

Pappano has an architecture full of details that suddenly converge on a hall

of amplified sound. Leading

the choir and orchestra of l’Accademia Nazionale Santa Cecilia, which he

conducts since 2005, Antonio Pappano creates a sound space without frontiers

where voices can live in intimacy and also in midst of the masses (few

operas have as many “asides” as this one), thus accepting the difficult

mixture proposed by the score which is so hard to balance. His conduction

enthralls us with the colorful encounters, the haziness, the internal

vibration and constant unrest of the atmosphere. If the scene at the Temple

of Vulcan —extremely well accomplished— puts all this together in the

contrasting levels of heroism and prayers, the preludes to Acts I and III

lead us to an iridescent musical environment that takes us through

undulating roads towards sensuality, mysticism and human passions that here

come into play, both frantic and subterranean. The building constructed by

Pappano has an architecture full of details that suddenly converge on a hall

of amplified sound.

Pappano also sustains the implicit theater of

voices, core of this artistic force that is opera. Anja Harteros is not the

spinto soprano one has in mind for Aida, on account of a somewhat narrow

middle, but her Ethiopian princess is perfectly well designed. Her careful

song joins the versatility of her accents, through which she manages to

capture the confusion of the character, her anguish, her haughtiness. She

outlines a fearful Aida, a contradictory lover who betrays, at times

treacherous, at times angelical. Formidable rival in the plot and also in

the vocal and scenic proficiency, Amneris is the opulent and vigorous mezzo

Ekaterina Semenshuck, with low tones that are a public menace with lewd

emphasis and who knows how to make the transition from the anger of the

working class to the impotence of one who cannot make herself loved.

Baritone Ludovic Tézier is a fine singer incapable of attempting against

music, and therefore his Amonasro never shouts; his fierceness is never

histrionic. He is successful even when he transfers ambiguity to this loving

father who is, above all, an uncompromising and inflexible king. Bass Erwin

Schrott isn’t Nicolai Ghiaurov or Matti Salminen, but serves with authority

as Ramfis. One must pay attention to the Sacerdotessa played by Eleonora

Buratto, whose current repertoire includes Adina (L’Elisir d’Amore) and

Micaela (“Carmen”), but perhaps may someday sing the main role of this opera

( a truly fledgling spinto?).

In the vocal level, the greatest

success of this version is the Radames of Jonas Kaufmann, dramatic and

lyrical alike, more of a lover than a hero, himself controversial. The great

German tenor knows how to reconcile ardor and refinement, and —artist of a

superior level— manages to instill into the optimism of his character

worrying and dark forebodings. His “Celeste Aida” is anthological due to the

impalpable abandonment of his singing and the B flat dreamt of by Verdi, in

mezza voce and morendo, conveniently avoided by most tenors. His whole

performance —beyond the depth of his low tones and the insolence of his high

tones— is a fabric of details and inflections, such as the diminuendo

introduced in “il ciel de’ nostri amori come scordar potrem?”, or that sweet

half-voice with which he travels over “O terra addio” with Harteros.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|