|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Classicalsource.com, 16

September 2009 |

| Richard Nicholson |

|

|

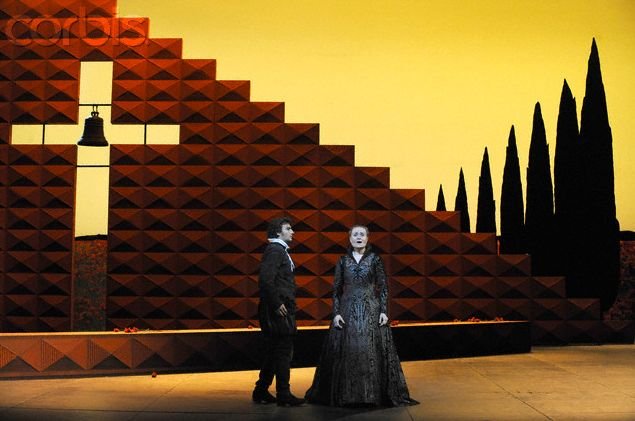

The Royal Opera – Don Carlo [Kaufmann, Keenlyside,

Furlanetto, Bychkov]

|

|

Photo: ©

Robbie Jack/Corbis |

This production is already taking on the

appearance of a classic as early as its first revival. A great deal of

artistic, particularly musical endeavour has been invested , which for a

successful performance of Verdi’s “Don Carlo” arguably needs more than the

four greatest singers in the world as stipulated by Caruso for “Il

trovatore”: five or six if you include the Grand Inquisitor would be nearer

the mark, not to mention the substantial role of the chorus and the fact

that, as a French grand opera, scenic spectacle and a wide variety of

musical styles have to be embraced and it is clear the heights to which the

Royal Opera is aspiring; no routine repertory opera this. This production is already taking on the

appearance of a classic as early as its first revival. A great deal of

artistic, particularly musical endeavour has been invested , which for a

successful performance of Verdi’s “Don Carlo” arguably needs more than the

four greatest singers in the world as stipulated by Caruso for “Il

trovatore”: five or six if you include the Grand Inquisitor would be nearer

the mark, not to mention the substantial role of the chorus and the fact

that, as a French grand opera, scenic spectacle and a wide variety of

musical styles have to be embraced and it is clear the heights to which the

Royal Opera is aspiring; no routine repertory opera this.

This is only the third production of this great but enigmatic work in fifty

years at Covent Garden. The legendary 1958 staging marked the centenary of

the present house and represented a collaboration between the

designer/director Luchino Visconti and the equally fastidious conductor

Carlo Maria Giulini. It was regularly revived for over forty years, by which

time the original trompe l’oeil sets had long lost their freshness. The 1996

Luc Bondy staging using the French text, originally displayed at the

Châtelet in Paris, was minimalist in scenic terms and that great

bass-baritone José van Dam was miscast as Philippe.

This revival of Nicholas Hytner’s production benefited from an outstanding

cast, even if a degree or two short of the highest level. Most

significantly, the switch to a more reliable exponent of the title role made

the relationships at the heart of the work more absorbing and not

sidetracked by vocal anxieties. The main attraction among the 2008 cast was

Rolando Villazón, who could be counted on to bring pathos to the role. He,

as is well known, has been going through a period of shaky vocal health,

with cancellations and spells of convalescence. A broadcast from the initial

run shows a portrayal of maximum intensity, with tone swollen by emotional

energy transmitted through vocal equipment perilously weak for it to bear,

something which tenor-watchers had feared and predicted since he came upon

the scene.

His successor Jonas Kaufmann has had a career roughly contemporary with

Villazón’s but has appeared to own a more robust instrument which allowed

him to sing within his resources. A couple of rusty high notes in his Act

One aria could easily be excused; an exquisite use of mezza voce announced

the singer had engaged with the sensibility of the character. For the heroic

declamation of the Act Three public scene he found sufficient weight of tone

to hold his own against his raging father, while the long, high lamenting

lines of the trio earlier in the Act rang out in powerful confirmation that

he realised a turning point had been reached in his life. He retained plenty

of stamina for the farewell duet at San Yuste.

Another newcomer to the production is the American Marianne Cornetti. The

original Eboli, Sonia Ganassi, basically a Rossini mezzo, though nimble

enough in the ‘Veil Song’, was stretched by the heavy dramatic writing

elsewhere. Heavy, dramatic mezzos are currently in short supply but Cornetti

is of the right sort, an Azucena and an Amneris. She was comfortable at both

extremes of the range in the ‘Veil Song’, which was a little restrained

vocally. Her jealous fury on discovering that Carlos’s affections lay

elsewhere was delivered in tone as impenetrable as teak. Conversely, her

remorse before the Queen was movingly conveyed and she offered a rip-roaring

‘O don fatale’. Marina Poplavskaya is a most promising lyrico-spinto soprano

with a glowing ruby-red middle and a hauntingly expressive chest register.

If her top notes do not yet always burst into flame she is probably right to

develop that sort of vocal excitement slowly.

Arguably Posa was the character for whom Verdi wrote his least progressive

music in the opera. Though the duet with King Philip in the Second Act

embodies the flexible form of evolving dialogue unconstrained by formal

rules that is characteristic of the mature Verdi, Posa has three other

solos, an elegant romanza in the monastery garden scene and two, one after

the other, in his death scene which are conventional. The big duet with

Carlo famously ends with a crude C major passage in thirds and sixths which

has long been held as a black mark against the composer, at least outside

Italy. I did not feel that the role particularly suits Simon Keenlyside, who

has made a distinguished career mostly in parts which are physically active

and in bold characterisations. Here he has to portray a resigned figure in

the prison scene, even if he did achieve the feat of singing most of ‘Io

morro’ lying with one cheek on the stage floor!

The central theme of the opera, to which the love interest is really

subordinate, is the battle between church and state. Ferruccio Furlanetto

dominated every scene except one in which he appears as King Philip. He

wants control and asserts it most obviously in his cruel dismissal of the

Queen’s lady-in-waiting. Even during his wife’s farewell to her he can be

seen casting sideways glances in her direction, looking for confirmation of

his suspicions about her. In the auto-da-fé scene his response to Carlos’s

appeals is withering. The cry of “Insensato” had me cowering in fright. His

colossal bass voice was firmly focused and his enunciation of the text

consistently lucid. I do not remember Christoff, Ghiaurov or Ramey producing

greater torrents of sound than this. The scene with Posa had found him

stalking the Marquis, getting right in his face when accused of resembling

Nero but the first signs of insecurity were present as his confided his

fears to him. The great aria, for which Semyon Bychkov set tempos noticeably

faster than usual, came from a nervy man rather than from a tragic figure

and only the final utterances were forcefully sung, The king’s weakness was

underlined by the following duet with the Grand Inquisitor, which he began

meekly kneeling. Then, when the Inquisitor went on the attack Furlanetto’s

tyrant was left completely trounced. He even met his match for vocal power

in this inspired piece of casting: The thunder of John Tomlinson’s Wotan

voice only faltered on a very few cloudy high notes.

The third bass role of the Monk was sung by Robert Lloyd in a voice

imperceptibly changed from his heyday. Whether this was a living human being

on his final appearance or an apparition was unclear. Pumeza Matshikiza was

a chirpy Tebaldo, prominent in every scene in which she appeared, while the

clean sound of tenor Robert Anthony Gardiner contains promise of a career in

the lyric repertoire to come. He and Eri Nakamura, a bell-like Voice from

Heaven, are members of the Jette Parker Young Artists Scheme. The Flemish

deputies made a positive effect vocally as well as dramatically.

Bychkov’s conducting matched that of his predecessor Antonio Pappano. His

handling of the orchestral commentary which Verdi writes, especially for the

duets in which the work abounds, was telling. The dramatic moments were

thrillingly done yet there was subtlety also. In the introduction to the

first scene of Act Three statements of the theme of Carlos’s opening aria

overlap; his encouragement of each group of players to produce a distinctive

colour in these sequences was a memorable moment in the performance. The

Chorus excelled itself to an exceptionally high level of vocal standard and

musicianship, which Choral Director Roberto Balsadonna is nurturing and

managing admirably. These singers’ ability to move smartly into position

before attacking their music impeccably was particularly noticeable in the

auto-da-fé scene, where the mob had to be corralled against the side wall at

the appearance of the monarch.

Nicholas Hytner’s production avoids the excesses of a ‘concept’ staging and

characterisations are incisively drawn. The central portrayal of Don Carlos

as immature is established in the first scene. He initially approaches

Elisabetta, then withdraws bashfully. They indulge in a playful chase with

the portrait. Yet there is an erotic daring about him, as he edges closer to

her off the two tree-stumps on which they are seated. It comes as no

surprise when his libido overflows in the Act Two duet. He stalks her; even

when the physical approach is repulsed he crawls over the ground, attempting

to trap her train. In the garden scene, expecting her arrival for an

assignation, he lies supine in an overtly sexual pose. I was perturbed by

his treatment of Posa’s visit to Carlos in jail, however: they pawed each

other in a way which suggested that the two men had more than a platonic

friendship. Can this have been intentional? Hytner’s handling of all such

encounters is responsive to the rhythms of the musical development and his

blocking of choral groups such as the ladies-in-waiting during the ‘Veil

Song’ thoughtful. The one big mistake is to add sound effects to the scene

in the square in Valladolid. The crowd’s shouts of enthusiasm drowned out

the stage band (its co-ordination with the orchestra in the pit was

extremely well-disciplined) while gratuitously abusing the heretics, each of

whom was offered the opportunity to repent by a supernumerary priest not

envisioned by the work’s creators.

Bob Crowley’s scenery has elements that are clearly symbolic, such as the

portcullis wall which descends repeatedly, cutting off Carlos and

emphasising his isolation. Mark Henderson’s lighting is less contentious,

the shafts of light piercing the gloom of the monastery highly evocative, as

is the lighting of Philip’s study, which left us wondering what might be

there in the murky depths of that large space.

While appreciating that The Royal Opera wanted to choose a complete version

of this score as approved by Verdi, rather than creating its own jigsaw of

the best bits from miscellaneous versions, I would have liked to see the

1866 introduction to Act One (cut before the première the following year),

in which the hardship suffered by the peasantry and Elisabetta’s compassion

are more strongly drawn (and in fine music), unlike the perfunctory

treatment they receive in the shortened version. The quiet ending of Act

Five with monks chanting which Verdi originally wrote also seems to me

preferable. As it stands, however, this is a triumph. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|