|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| El Mercurio, 5 DE JULIO DE 2014 |

| POR JUAN ANTONIO MUÑOZ H. |

|

|

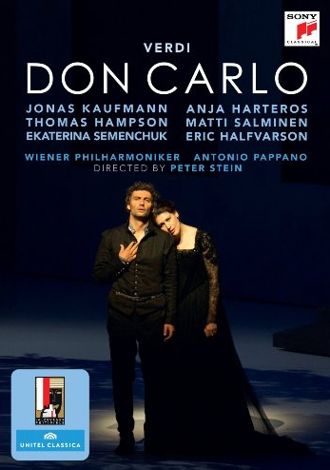

Un “Don Carlo” de referencia

|

|

Don

Carlo” (Verdi) es la ópera que nadie puede imaginar, pues cada

representación parece única: es muy difícil dar con una puesta en escena

de la obra completa. Casi hay tantos “Don Carlo” como puestas en escena

se han hecho. Incluso hay cambios entre la versión del estreno en París,

en 1867, y las funciones realizadas dos días después. También están las

“ediciones” de 1872, firmada en Nápoles, y las de 1884 (hecha para

Viena) y 1886 (Módena). Esta última excluye el ballet. En general, hoy

se distingue entre la versión francesa de 1867 y la italiana de 1884,

con libreto de Zanardini y De Lauzieres. Don

Carlo” (Verdi) es la ópera que nadie puede imaginar, pues cada

representación parece única: es muy difícil dar con una puesta en escena

de la obra completa. Casi hay tantos “Don Carlo” como puestas en escena

se han hecho. Incluso hay cambios entre la versión del estreno en París,

en 1867, y las funciones realizadas dos días después. También están las

“ediciones” de 1872, firmada en Nápoles, y las de 1884 (hecha para

Viena) y 1886 (Módena). Esta última excluye el ballet. En general, hoy

se distingue entre la versión francesa de 1867 y la italiana de 1884,

con libreto de Zanardini y De Lauzieres.

Este título mayor de la

producción verdiana vive en un tapiz de contradicciones: la trama reúne

a personajes históricos, pero todos ellos están al servicio de una idea

que no se interesa en la historia verdadera; al momento del estreno se

acusó al compositor de dejarse influir por Meyerbeer y por Wagner, sin

embargo la partitura es ejemplo del Verdi más profundo y complejo, y si

bien exige un gran espectáculo, su alma se encuentra en las escenas

íntimas. A todo aquello hay que agregar que, a pesar del conflicto

amoroso, se trata de una ópera política que muestra a un duro rey

(Felipe II de España) finalmente dispuesto a hablar de libertad y de

abrir su corazón a un rebelde (Rodrigo de Posa), y que cuestiona la

injerencia de la Iglesia Católica en las decisiones de Estado.

Resta el amor, aquí traicionado, como también lo está el deseo: Isabel

de Valois se casa con Felipe aunque está enamorada del hijo de este,

Carlo; Felipe ama y sufre por una mujer a la que sabe enamorada de su

hijo; Carlo ama a su “madre”, como llama a Isabel, y pone a competir la

disputa amorosa que tiene con su padre con las diferencias que tiene con

él en términos de gobierno; la Princesa de Éboli ama a Carlo y por eso

termina denunciando a Isabel. Además, el mejor término para describir la

relación entre Carlo y Rodrigo es “bromance”; su amistad imbatible se

demuestra con la inmolación de Posa. Él y Carlo desean una libertad que

nunca han vivido; parecen amarse en ese deseo de libertad.

Hay

varios aspectos que permiten decir que este es un “Don Carlo” de

referencia. Montada en Salzburgo en 2013, es la versión en cinco actos

de la traducción italiana, sin el ballet pero con la escena del tercer

acto en que Isabel y Éboli intercambian vestidos, que no se encuentra en

la mayor parte de las ediciones discográficas. Peter Stein —director de

teatro que fundó el Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, compañía de vanguardia

de las tablas alemanas— opta por una puesta con elementos tradicionales

basada en un cuidado trabajo de actores que exuda preguntas sobre la

naturaleza de las relaciones privadas en conflicto, pero que también

asume posiciones respecto de los abigarrados conflictos políticos y

religiosos que aborda el libreto. Sustenta

su trabajo apoyado por una

escenografía funcional, despojada y con delicadas alusiones a la España

del siglo XVI; luces que producen cuadros crepusculares sugestivos, en

especial para la soledad de Carlo y para sus dúos con Isabel y Rodrigo;

un vestuario lujoso con Diego Velázquez como referencia, y un sexteto de

cantantes que sabe que no basta con tener voz.

Desde el foso, el

maestro Antonio Pappano dirige con pasión, consigue plasmar las sombras

que habitan esta difícil partitura y logra clímax sonoros en el

crescendo del dúo de amor entre Carlo e Isabel del primer acto, en la

pasión ambigua que consume a Rodrigo, y en el enorme concertante del

Auto da Fe.

El Infante del tenor Jonas Kaufmann es un príncipe

desposeído y melancólico, un héroe vulnerable y enfermo hecho luces y

tinieblas a través de una voz oscura y bruñida que turba con su ternura

y belleza, y que deslumbra con el uso magistral de la messa di voce.

Anja Harteros canta una Elisabetta di Valois que es pura nobleza en la

actitud y rigor en el fraseo, características que también se encuentran

en Thomas Hampson (Rodrigo de Posa), cuyo esmalte vocal no es el mismo

que hace algunos años, pero que es un artista sensible y musical como

pocos. Ekaterina Semenchuk —sucesora natural de la estirpe Obraztsova y

Borodina—impone su Éboli gracias a un canto voluptuoso e intenso,

mientras que dos veteranos sin parangón,

los bajos Matti Salminen (un

maestro del canto declamado) y Eric Halfvarson (terrorífico), hacen del

enfrentamiento entre Felipe II y el Gran Inquisidor una clase de tensión

teatral. Sony

Classical, 2014. 2 Dvd.

|

|

| Translation: |

|

| A “Don Carlo” of

reference |

|

|

“Don Carlo” (Verdi) is the opera that no one

can imagine, as each performance seems unique; it is very difficult to

find a staging of the complete work. There are almost as many “Don Carlo”

as there are stagings of it. There are even changes between the version of

the première in Paris, in 1867, and those performed two days later. There

are also the “editions” of 1872, signed in Naples, and those of 1884 (made

for Vienna) and 1886 (Modena). This last one excludes the ballet.

Nowadays, there is generally a distinction between the French version of

1867 and the Italian one of 1884, with libretto by Zanardini and De

Lauzieres.

This major title of the Verdian production lives within

a tapestry of contradictions: the plot gathers historical characters, but

they are all at the service of an idea that is not interested in the real

story; at the time of the première the composer was accused of being

influenced by Meyerbeer and Wagner, but the score is an example of the

most profound and complex Verdi, and although it demands a great show, its

soul is to be found in the more intimate scenes. To all of the aforesaid,

we have to add that, despite the love conflict, it is a political opera

that shows a hard-hearted king (Filippo II di Spagna) who is finally

willing to speak of freedom and to open up his heart to a rebel (Rodrigo

de Posa), and challenging the interference of the Catholic Church in State

decisions.

There still remains love, here betrayed, as well as

desire: Elisabetta di Valois marries Filippo although she is in love with

his son, Carlo; Filippo loves and suffers on account of a woman who he

knows is in love with his son; Carlo loves his “madre” (mother), as he

calls Elisabetta, and makes the love conflict he has with his father

compete with the differences he has with him in terms of government; the

Princess of Éboli loves Carlo and that is why she ends up by denouncing

Elisabetta. The best term to describe the relationship between Carlo and

Rodrigo is “bromance”; their unbeatable friendship is demonstrated with

Posa’s immolation. He and Carlo wish a freedom they have never lived; they

seem to love each other in that desire for freedom.

There are

various aspects that allow us to say that this is a “Don Carlo” of

reference. Staged in Salzburg in 2013, it is the version in five acts of

the Italian translation, without the ballet but with the scene in the

third act in which Isabel and Éboli exchange dresses, which is not to be

found in most of the record editions. Peter Stein —theatre director who

founded the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, a cutting-edge company of the

German theatre— opts for a staging with traditional elements based on a

careful work of the actors, oozing with questions about the nature of the

conflicting private relationships, but which also takes a stand on the

variegated political and religious conflicts addressed by the libretto. It

supports their work with a functional and naked staging, with delicate

allusions to the Spain of the 16th century; lights that render suggestive

twilight pictures, especially for the solitude of Carlo and for his duets

with Isabel and Rodrigo; a luxurious wardrobe with Diego Velázquez as

reference, and a sextet of singers who know that having a voice is not

enough.

From the pit, Maestro Antonio Pappano conducts with passion

and manages to capture the shadows inhabiting this difficult score,

achieving sonorous climaxes in the crescendo of the love duet between

Carlo and Isabel in the first act, in the ambiguous passion that consumes

Rodrigo, and in the huge concertante of the Auto da Fe. The Infante of

tenor Jonas Kaufmann is a dispossessed and melancholy prince, a vulnerable

and sickly hero rendered light and shadows through a dark and burnished

voice that disturbs with its tenderness and beauty, and dazzles with its

masterly use of the messa di voce. Anja Harteros sings an Elisabetta di

Valois who is pure nobility in the attitude and rigor in the phrasing,

features that are also to be found in Thomas Hampson (Rodrigo de Posa),

whose vocal enamel is not the same of recent years, but is a sensitive and

musical artist like few others. Ekaterina Semenchuk —natural successor of

the Obraztsova and Borodina lineage— imposes her Éboli through a

voluptuous and intense singing, while two unparalleled veterans, basses

Matti Salminen (a master of declaimed singing) and Eric Halfvarson

(terrifying), render the confrontation between Filippo II and the Grand

Inquisitor into a lesson in theatrical tension.

Juan Antonio Muñoz

H. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|